“It has flowers and thorns, dust and roses, mud and sandal, it also has beauty and ugliness – I could not get away from anything.” ~ Phanishwar Nath Renu’s self note about the book.

Maila Aanchal, composed by Phanishwar Nath Renu, is one of the best novels in Hindi literature after Premchand’s Godan. Publication of this novel during 1954-55 was almost like a phenomenon in Indian literature. Since then it has been adopted in many theatre plays and performance forms. A decade later, in 1966, a film (Teesri Kasam) starring Raj Kapoor and Waheeda Rahman was made based on his short story Mare Gaye Gulfam. In his short and illustrious career, he wore many hats- including that of a politician, an activist, a poet, and a writer- before he died at a young age of 56 in Patna, Bihar.

In the backdrop of a remote rural area of north-eastern Bihar, bordering Nepal and Bangladesh, Maila Anchal portrays a very vibrant and articulate life of the region and its people with whom he was intimately connected. The charm of this novel is that its protagonist is not a person or a character but the entire region. At a time when the world was invested in the idea of ‘world literature’, Renu chose to emphasize on the word ‘region’. The regional for him, however, was never meant to be parochial; it used the classics of folks and elements of everyday rural life to highlight the nuances of a place he knew and had experienced.

The novel’s prose has a serene musicality to itself. He brilliantly used sounds of different music instruments( sometimes for jumping from one scene to another) and folk songs metaphorically to create a story that not only described the phenomenal change rural India was witnessing post-independence but also how all of this was affecting the consciousness of people.

The young doctor Prashant, after completing his education, chooses a remote village as his field of work, and in this sequence faces the challenges of rural life, of grief, lack of information, ignorance, and superstition. He is intrigued by the sufferings and struggles of the people trapped in various forms of social exploitation. I believe that most of us still see this circumstance repeating itself; hence after sixty-five years of its publication, the novel still does not seem to have lost its relevance.

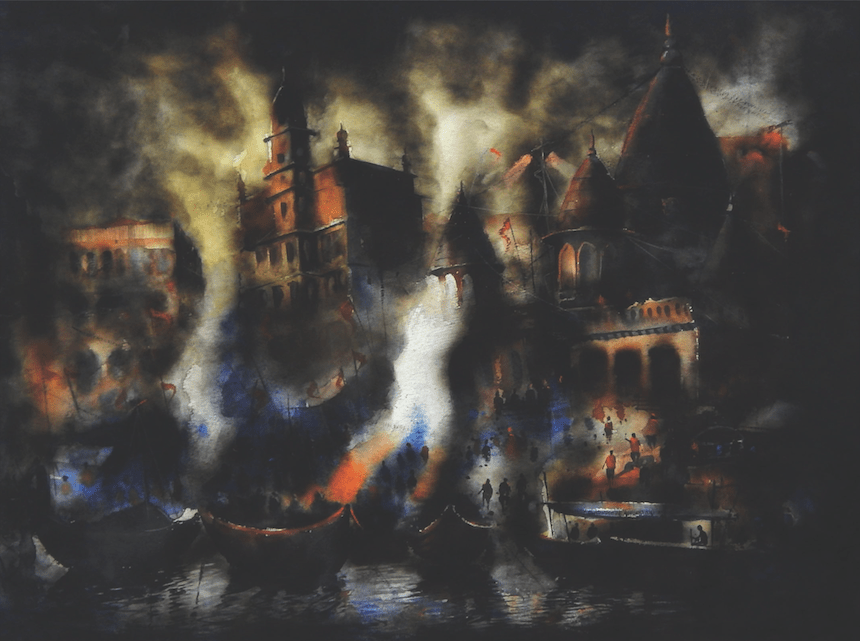

The story is set in a small town called Maryganj. A British officer associated with indigo cultivation W.W. G. Martin’s wife’s name was attached to this district. Very similar to the days we are witnessing now during the COVID-19 global pandemic, the novel begins with this overall backdrop of the Malarial & Black Fever epidemic situation the entire region was facing during the colonial time. Mary, who was Martin’s second wife and for whom Martin had made a Kothi, could not enjoy the privilege for a long time. She got infected with Malaria and died soon. Trying to open a malaria center in Meriganj while he was alive, Martin couldn’t bear the grief and died afterward. With this, the Indigo Age in India also ended.

In post-independent India, Prashant kept on researching for medical advances, struggling with casteism and other social discriminatory practices that were in place and aching for his love for kamli. Vishvnath, Kamli’s father kept on behaving with his complicated character of an opportunist and a mindful, jolly person at the same time; Politicians were still trying to cook their bread in this heat of chaos and dysfunctionality of the governance systems. The disproportionate distribution of power and resources were pushing people to often take shelter in violence.

After so many years sometimes I feel like we are reliving the same stories over and over again. Finally like our everyday prayers these days, the story ends with a hopeful sign that the collective-consciousness that has been sleeping since ages is waking up fast.